The 2000s have been an eventful period from the standpoint of global finance. Most conspicuous are the two instances of the global recession, one in 2007/08 and the second one still unfolding now. In both of these instances, central banks worldwide have had to go outside the ordinary to restore calm.

Central banks have several tools they could deploy to combat the recession. Traditionally, the crudest tool has been lowering interest rates. But what happens when the crudest tool does not work? Well, you go for an unconventional tool that is even cruder.

This is what happened in the aftermath of the 2007/08 Great Recession. The United States Federal Reserve reduced the target federal funds rate to near zero to bolster financial market conditions. Instead, the economy continued to tailspin to the point that the Fed had to go for a nontraditional policy called quantitative easing (QE).

Quantitative easing explained

Quantitative easing is a technical term that describes a monetary policy that entails printing money to purchase assets in distress. The asset purchase often happens on a large scale. For example, from March 2009 through March 2010, the US Fed purchased $1.25 trillion and $200 billion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and federal agency debt, respectively.

The purpose of the asset purchase was twofold. Purchasing mortgage-backed securities would support the housing market through thawing the frozen mortgage lending sector. Recall that the housing market bubble fueled by sub-prime lending, which backed the MBS, was singled out by scholars as one of the Great Recession causes.

Secondly, purchasing federal agency debt would further stabilize the mortgage lending market. Why? Most of the federal agency debt (debts issued by Freddie Mac, Fannie Mae, etc.) had gone into funding the purchase of mortgage loans.

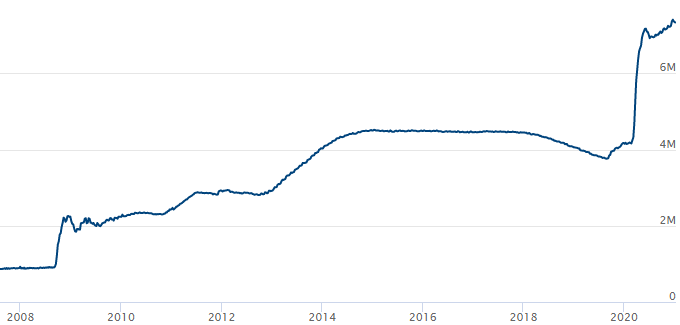

Faced with another recession as part of the coronavirus pandemic impact, the Fed set in motion another round of QE. This time, the program was so massive that the Fed’s balance sheet had swollen by a little over $4 trillion in six months. By January 12, 2021, Fed’s liabilities stood at about $7.3 trillion.

How does QE work?

Understanding how QE works will help us to tie it to the concept of inequality. QE is a nontraditional monetary policy for starters, but the way it works is reminiscent of the traditional monetary policy tools.

QE delivers its impact on the economy by initiating changes in long-term Treasury securities yields. The Fed’s target was for the QE to induce a decrease in the interest rates of the Treasury securities and other financial instruments as desired. Why so? Perhaps we need to digress for a moment to explain why the Fed aims for higher long-term yields.

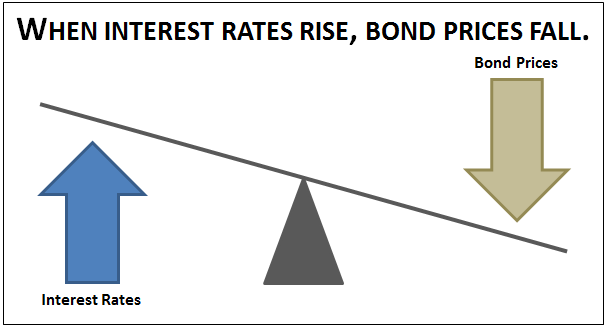

Bonds, in general, have two very important aspects, price, and yields. The price and yields (interest rates) of bonds have an inverse relationship. An increase in the price of a bond corresponds with a decrease in the interest rates of the bond. Conversely, a decrease in the price of a bond corresponds with an increase in interest rates.

So, why would the Fed want a large scale asset purchase in the first place? QE increases the demand for the assets that the Fed targets. For example, it increased demand for MBS and US Treasurys in 2009. The swelling of buyers then pushes the assets’ prices up, which has the opposite effect on interest rates, as the figure above suggests.

As bonds’ interest rates fall, business financing becomes cheaper. Businesses can now initiate capital investments on a large scale, and the new investments should – in the long-run – stimulate economic activity and create new jobs.

The link between QE and income inequality

When the Fed initiated the first QE (QE1) in 2009, the primary aim was to bolster the banking system’s resilience, thereby forestalling insolvency and illiquidity in the economy. The other objectives were to stimulate economic activity and to mitigate deflationary tendencies in the US economy.

But QE directly affected the first objective alone, meaning the Fed relied on companies and financial institutions to attain the remaining objectives. All of a sudden, the private sector had tons of cheap money on their hands, which ostensibly would go into capital investments.

For a long time, the US labor market has buckled under the weight of globalization and political and legal reductions in labor bargaining power. As a result, the economy was facing long-term wage stagnation when QE kicked in. So, what did the wealthy class – the people who own the financial institutions and companies the Fed expected to help it achieve its objectives – do?

The wealthy individuals redirected the influx of cheap money to short-term assets such as the stock market. This is why the US stock market has touched several record highs since 2011.

As stock markets soared, wages continued to stagnate, meaning the working-class Americans could not partake in the rising wealth. Wealthy individuals have better access to financial markets than low-income earners.

Worse still, the coronavirus pandemic pushed many people out of jobs as companies closed down. Therefore, it seems counter-intuitive that the Fed expects companies that are not operating or have cut down on operations to transmit liquidity to the rest of the economy.

Conclusion

One question sticks out. Did QE succeed? To a certain extent, yes, it did. It did succeed in preventing a total breakdown of the global economy. On the other hand, QE did not succeed in lifting all economic participants out of recession. For example, many low-income earners lost jobs, meaning companies and financial institutions could not transmit QE’s liquidity to them.

Also, low-income earners have a problem accessing the stock market because of soaring prices. In the end, only wealthy individuals could take advantage of the swelling equity prices to get richer.

Leave a Reply